- History Home

- People, Leadership & Service

- A Legacy of Excellence

- History & Impact

- Meetings Through the Years

- Resources

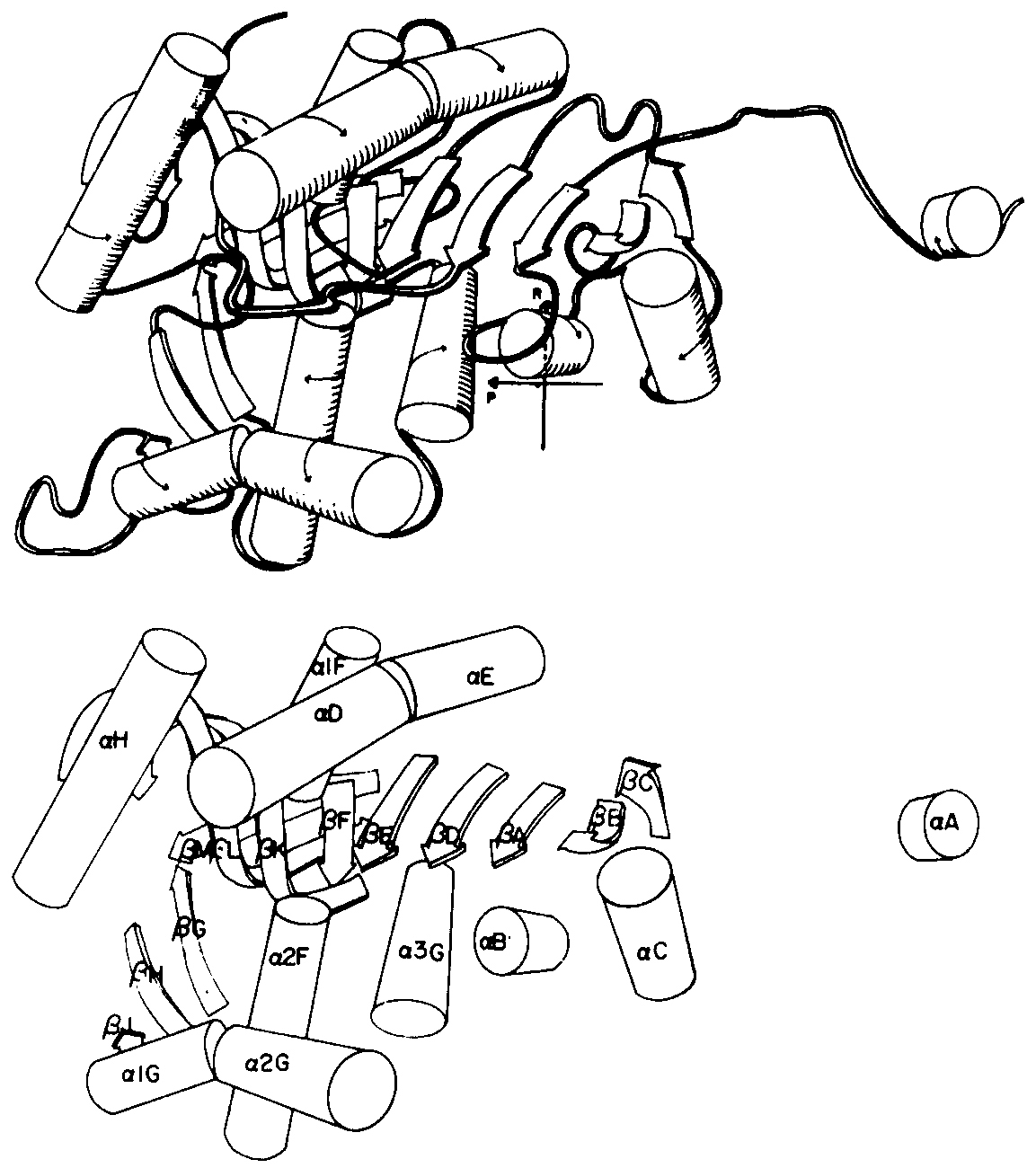

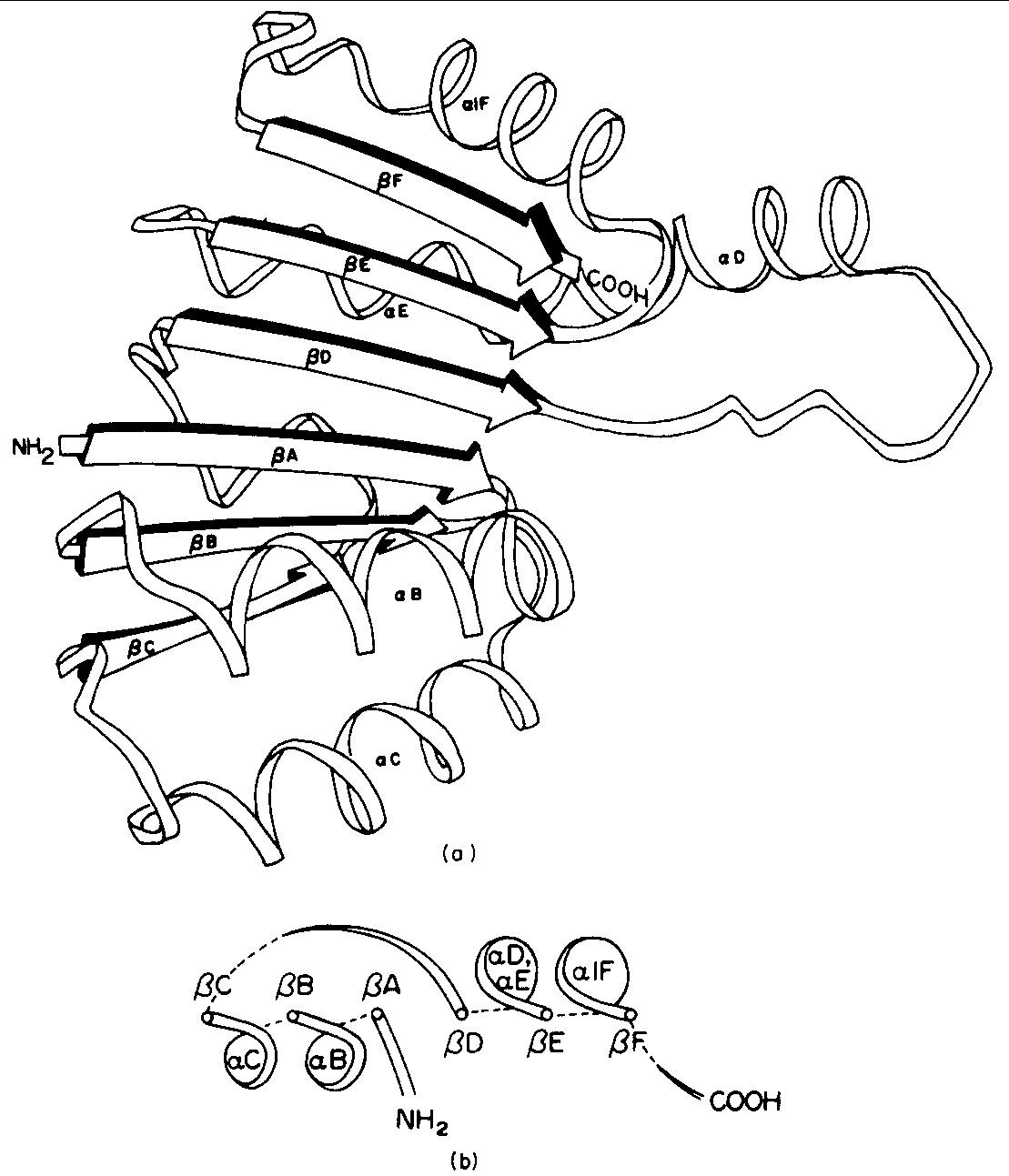

Audrey Rossmann (1928-2009): A Personal TributeHistorically, little attention has been paid to the spouses of high profile scientists and the role that they have played in the accomplishments of their companions. I can refer to Mme Lavoisier, less known as Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze, who diligently worked with her husband (the illustrious chemist) in writing experimental protocols, illustrating his chemical apparatus and so many other contributions; yet she remains an unknown contributor to the history of science. I can also mention Marie Laurent, who became Mme. Louis Pasteur, another woman devoted to the absorbing science of her husband and probably known by very few. I do hope that some scholarly research is done on this area to enrich our lives and change our perception of famous scientists as laboring alone in the laboratory, their companions providing only the domestic support. Audrey Rossmann contributed and was devoted to Michael’s work in many different ways. She provided an artistic balance and complement to the gallery of structures that he and his colleagues unveiled over the years at the Department of Biological Sciences at Purdue University. In doing so, she had her own tangible ‘structures’ to present to the world. Older generations of protein crystallographers may remember the first ‘cartoon’ sketches of the meanderings of the polypeptide chain in lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) and the Rossmann fold. These classic representations (shown here) were drawn by Audrey Rossmann at the suggestion of Anders Liljas (at that time a Swedish postdoc in the lab). Similar renderings of the different protein folds were popularized by Jane Richardson in her own unique style. Nowadays, computers do the drawings in a more timely and efficient manner, but certainly with very different artistry.

After the milestone of the LDH structure in Michael’s lab, the structures of viruses began to appear. First Southern Beam Mosaic Virus (SBMV), a humble plant virus, and later Rhino (HRV), the first human virus to be solved at atomic resolution. The theme of virus structure and symmetry was quickly picked up by Audrey in her pottery work, clothes and other artistic creations. I still treasure in our own yearly Christmas tree decoration ritual, hanging the virus-like adornment that Audrey gave us in 1982.

Members of the laboratory often received a pottery memento of their stay in the lab. A most precious gift is the ‘virus-within- a-virus’ ceramic piece that Michael and Audrey gave Victoria and me as a goodbye present when we departed from the lab in 1985. It is decorated on the outer shell with the signatures of people in the lab at the time, the projects I worked on and the triangular faces were painted with brown and black earthly colors. Floating inside is another full sphere triangulated with the faces of an icosahedron. I remember Audrey bringing the pieces to the lab in a tray for the people to sign, with the inside sphere wrapped inside a newspaper, ready to be fired in the kiln. I never thought that this piece would become a treasured memory of her.

There is another way in which Audrey graciously supported Michael’s science as only she could do. She tirelessly hosted students, postdocs, colleagues and collaborators and their families at dinners, lunches, and brunches in their home and in spring, summer and fall at seasonal barbecues at various park venues around Lafayette and its surrounding areas in the outdoors that both Audrey and Michael always loved so much. Audrey has left an indelible mark on a multitude of people that were fortunate enough to meet her. –Cele Abad Zapatero |