- History Home

- People, Leadership & Service

- A Legacy of Excellence

- History & Impact

- Meetings Through the Years

- Resources

Obituary - Max Perutz (1914 - 2002)Obituary | Publications | Curriculum Vitae | Videos | Slides | Articles Max Perutz (1914 - 2002)

Early on Wednesday, 6th February, Max Perutz died of cancer after a long and productive life. Starting a Ph.D. in 1936 under J.D. Bernal at the Cavendish Laboratory, he applied X-ray crystallography to proteins and in 1953 developed the method of isomorphous replacement using heavy atoms to solve the phase problem. This led to the solution of the first protein structures, those of myoglobin by his colleague John Kendrew and his collaborators, and of haemoglobin by Perutz and his collaborators. For this, Perutz and Kendrew were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. With a great deal more work during the 1960’s, Perutz and his colleagues went on to solve the atomic structures of both oxy- and deoxy-haemoglobin which allowed him to propose a stereochemical mechanism for the cooperative binding of oxygen to haemoglobin. Max was the first author of a recent review (Ann. Rev. Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure 1998) of cooperativity in haemoglobin in which he noted that his mechanism still appeared to be correct. In more recent years, he worked on ligand binding to haemoglobin to help develop a clinically useful drug for increasing oxygen delivery to hypoxic tumours for radiation therapy, and to infarcted tissues. He also developed a strong interest in the structure of the polyglutamine tracts in Huntington’s disease. In his youth, as a sideline, he also worked on glaciers. He studied the transformation of snowflakes that fall on glaciers into the huge single ice crystals that make up its bulk, and the relationship between the mechanical properties of ice measured in the laboratory and the mechanism of glacier flow. He was a prolific and talented writer of popular articles and book reviews, many published in the New York Review of Books. He also wrote a number of books, including “Is Science Necessary” and “I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier” which are collections of essays. “Science is Not a Quiet Life” published by World Scientific Publishing is essentially his scientific autobiography.

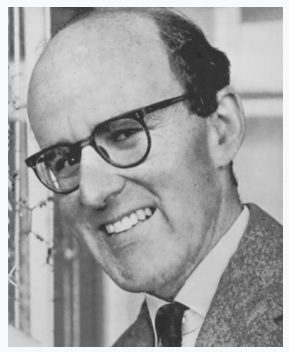

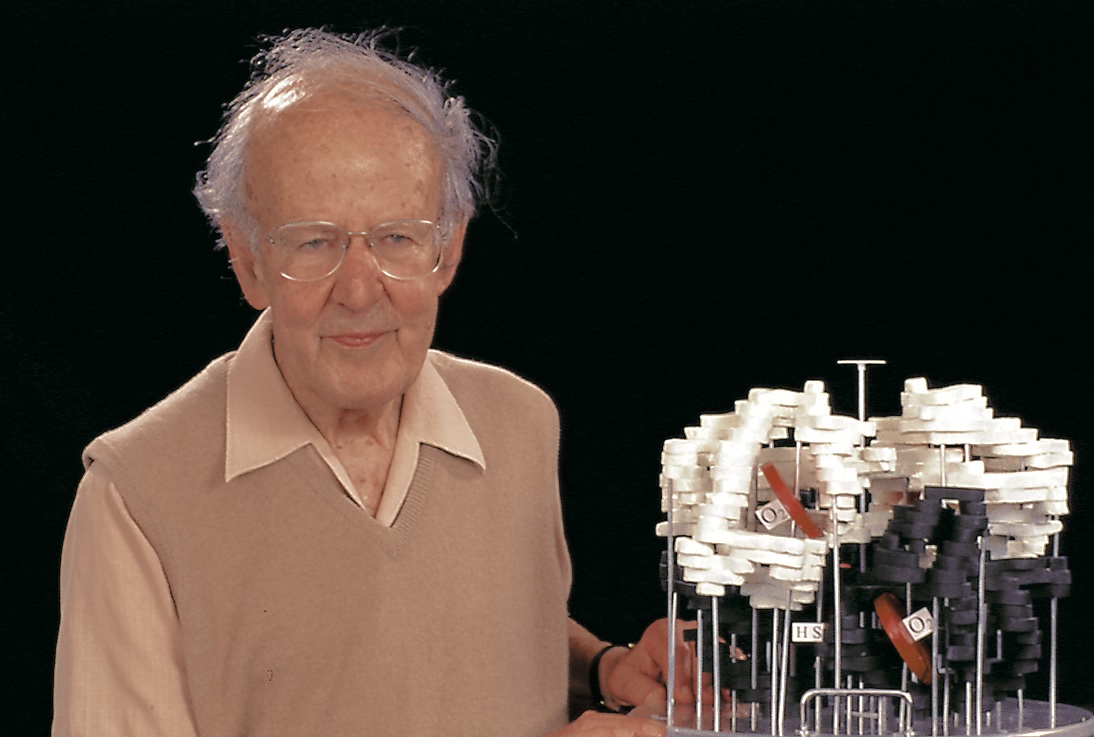

Max with Jeanne Perry at a gathering in David Eisenberg's back yard when he visited their UCLA laboratory in 1991.

At the Cavendish Laboratory with the support of Professor Lawrence Bragg and with his first Ph.D. student, John Kendrew, who joined him in 1945, he built up a group working on the molecular structure of biological systems which grew to four people in 1950 and to about 40 people by 1960. Merging then with other groups from Cambridge and London to create the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology on the Hills Road site (now Addenbrooke’s) in 1962, he became Chairman of the new Laboratory until 1979 when he “retired.” Since then he has worked nearly every day in the Laboratory which has grown to house over 400 people. Over the years, the Laboratory has been a prolific source of discoveries and inventions. In addition to his own research achievements, Max will be remembered for his interest in and warm support of the work of others, and as one of the founders of Molecular Biology. - from the web site statement of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

Professor Sir George Radda, Chief Executive of the Medical Research Council, said: “Our heartfelt sympathies go out to his family at this difficult time. Not only have his colleagues, at the MRC and in the scientific community lost a great co-worker and friend, but Britain and the world will be mourning the loss of one of the 20th century’s scientific giants.” “The impact of Max’s work remains a foundation on which science is being undertaken today. His Nobel Prize winning work on protein structure is more relevant now than ever as we turn attention to the smallest building blocks of life to make sense of the human genome and mechanisms of disease.” “Max had many interests and a great love of music and will be remembered as much for his science as for his endless drive and passion for knowledge and better communication of research. He was recognized as a great communicator himself. His books and book reviews stand up as good literature as well as good science.” “He was still working on research projects and publishing work in his 80s. Once asked why he didn’t retire at 65 he said he was tied up in some very interesting research at the time. This sums Max up well. He continued as a ‘retired’ worker after 1979, publishing over 100 papers and articles during his retirement. Until the Friday before Christmas, he was active in the lab almost every day, submitting his last paper just a few days before then.” “He has inspired countless young scientists and encouraged them to communicate their research in plain language to those whose lives are changed through their work. He will be sorely missed, but his life and work will continue to shape science and motivate new generations to understand the way the body functions and how this will help us manage health and disease.” - from the MRC statement on his death * top photo courtesy of Wikipedia (2020) |