- History Home

- People, Leadership & Service

- A Legacy of Excellence

- History & Impact

- Meetings Through the Years

- Resources

Biography - Walter Friedrich (1883–1968)Biography | Publications | Curriculum Vitae | Videos | Slides | Interviews | Articles | Obituary THE BIRTH OF X-RAY DIFFRACTION: EXCERPTS FROM A 1963 INTERVIEW WITH WALTER FRIEDRICH

By Professor Peter J. Heaney, Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University

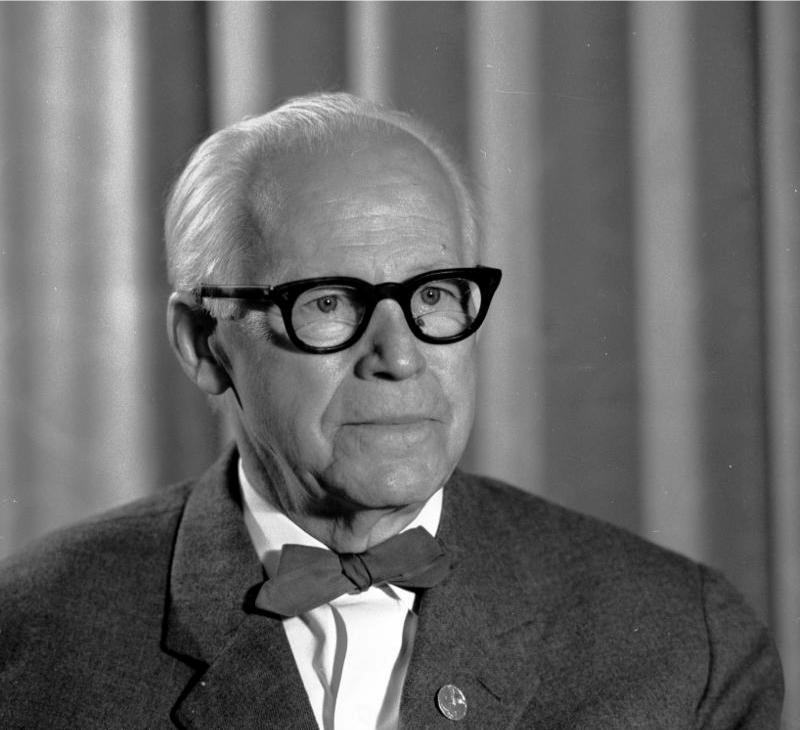

Walter Friedrich (1883–1968) was the first person to build a device that successfully achieved the diffraction of X-rays by a crystal, and he was the first to observe the diffraction pattern produced by it. This epochal accomplishment simultaneously demonstrated the wavelike nature of X-rays and the translational symmetry that defines crystallinity. Had Friedrich performed this study today, he might have been named a cowinner of the Nobel Prize. Instead, Friedrich’s status as a postdoctoral researcher on temporary loan from Arnold Sommerfeld to a privatdozent, Max von Laue, situated Friedrich on the lower rungs of the German academic hierarchy. Consequently, von Laue was named the sole recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914, and Friedrich’s contributions seem eclipsed by the likes of the Braggs père et fils, Paul Ewald, Peter Debye, and von Laue himself.  Walter Friedrich in 1962. Copyright German Federal Archive, Bild 183-A0919- 0015-001. Creative Commons license.

Friedrich recounted the story of the discovery in several published documents, including a decadal anniversary paper in Naturwissenschaften (Friedrich 1922, 363) and a reminiscence in the same journal 27 years later (Friedrich 1949, 354)—both in German. His impressions were not included among the personal remembrances in the semicentennial volume edited by Paul Ewald (Ewald 1962). Then Thomas Kuhn and colleagues spearheaded the Archives for History of Quantum Physics (AHQP) project in the 1960s to “find and preserve primary source materials for the study of the history of quantum physics” (Kuhn et al. 1967). Perhaps to correct the omission in Ewald (1962), Gustav Hertz, Théo Kahan, and John L. Heilbron traveled to East Berlin to interview Walter Friedrich in May 1963. Hertz (1887–1975) had collaborated with James Franck on inelastic collisions of electrons in gases, for which he won the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics. Théodore Kahan (1904–1984) was a French physicist who authored two dozen books on radioactivity and quantum physics. John Heilbron (b. 1934) was working on his doctoral studies with Thomas Kuhn at the time of this interview. He is now a professor of history and vice-chancellor emeritus at UC Berkeley.

With the assistance of Dr. Melanie Kaliwoda (Ludwig-Maximilians- Universität München), I have translated and annotated this interview. The full interview with preface appeared originally in Heaney and Kaliwoda (2020). The original interview and its translation also are archived with the AIP Niels Bohr Library & Archives. You can read the original interview in German at https://repository.aip.org/islandora/ object/nbla:266548. The translated and annotated interview is available at https://repository.aip.org/islandora/object/nbla%3A315886.

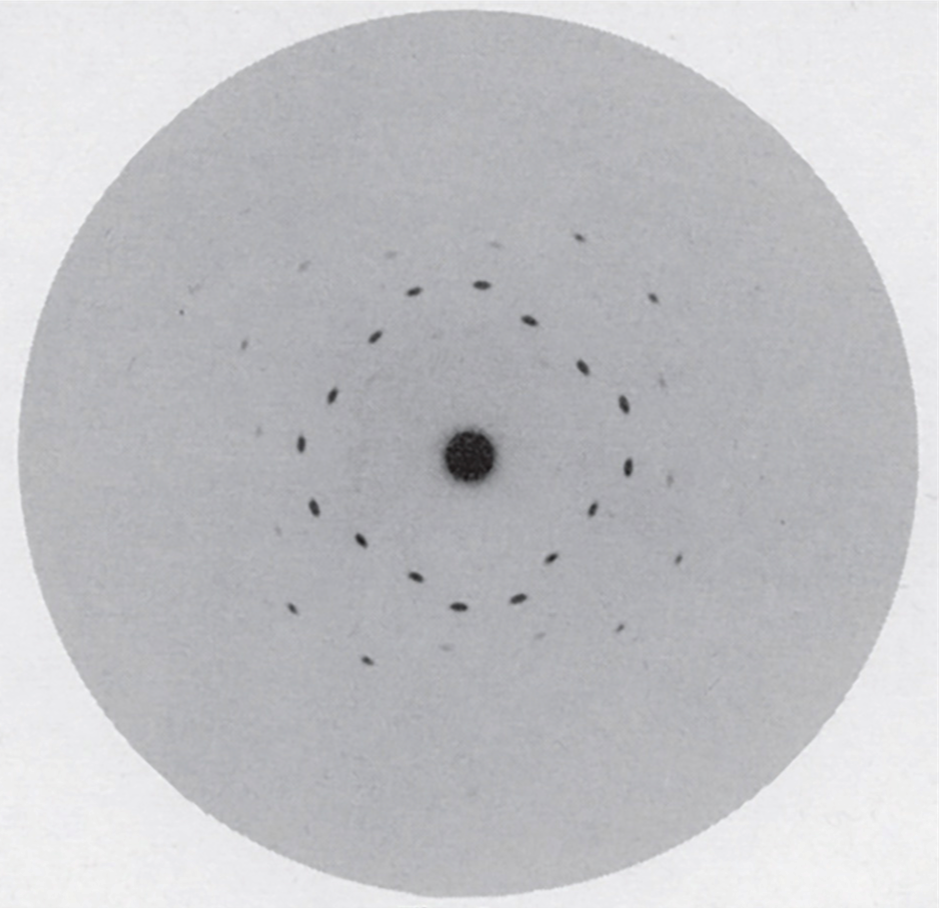

Excerpt from Interview with Walter Friedrich Conducted by: Gustav Hertz, John L. Heilbron, and Théo Kahan Place: East Berlin, East Germany Date: May 15, 1963 Walter Friedrich: ...At this time, Laue came up with the idea: If the X-rays have a wavelength as short as was assumed based on diffraction experiments with narrow slits, then they would have to give X-ray interference patterns when passing through an electron lattice, through a crystal. This was discussed for about a quarter of a year in the cafés, as was the custom in Munich at the time. Théo Kahan: Who was there? WF: Ewald and Laue. TK: You were there too? WF: No, I wasn’t there at all. I heard about it from their later conversations. I had a job studying X-rays with Sommerfeld. I had an X-ray machine, at that time, one of the most intense and powerful X-ray machines, and I had to do some work on particular properties of X-rays and Planck’s quantum theory, okay? …And we talked about it [X-ray interference] for a long time, and the strange thing is that none of the people who were at the meetings, including Röntgen, and Sommerfeld—also Mie when we were skiing, and Starke, (and Wald and Jort)—these were the main people at the time—they didn’t think it would work... And it was kind of forbidden to do an experiment. “This is not possible; it is superfluous; the thermal vibrations will prevent it [X-ray interference] from happening.” No, people have forgotten, but as we now know, there were statistical problems too. There was only a certain probability that the locations and positions of atoms according to the space lattice were regular, and it seemed like a longshot, you know, that we would observe interference; as we later proved, we needed long exposure periods. And we talked about it, and I said to Laue, “Well, let’s do it in the back [of the lab], let’s do it in the evening,” all right? [Chuckles]. And since, as I said, during the day I was busy with my work with Sommerfeld, my seminar assignments—you know what it is like in an institute—we brought in another student, Paul Knipping. He had just finished his PhD work and was writing it up and had some time. We built a very simple apparatus... Since we had misconceptions about the nature of these interferences, we first thought—and we should have known better, by the way—that it was the characteristic radiation of the crystal that triggered the interference. That is why we examined copper sulfate, because we thought we were generating the characteristic radiation of copper. Today, we know that this radiation is not at all coherent—just as fluorescent radiation is not optically coherent. As such, no interference could have come from the copper radiation. Anyway, because I knew about X-rays, I thought, “Well, let’s just irradiate the crystal for ten hours.” So we irradiated for ten hours... And in the evening, it was around 11 p.m. that I took the plate out and put it in the developer tray, and then suddenly a black blob emerged, a black spot from the unscattered X-rays. In addition, there were ring-shaped patterns that were quite irregular, of course, because firstly, the mineral belongs to an irregular crystal system, okay, and also because it was not oriented. And next to these patterns, there was the shadow of a pitcher [Laughter]. TK: A pitcher? WF: A mug, a Munich mug, a beer mug. And how did that come about? Because the nondirectional radiation, the scattered radiation, cast a shadow of a so-called screw-ring. The crystal was inserted into this screw-ring. This shadow appeared on the plate as a body, short and wide, and the handle on the ring also stuck out. Now, of course, you can imagine my great surprise. I went to Knipping in the morning, and we went to Laue and then finally to our boss and showed it to him... We then had a jeweler cut a beautiful plate from a sphalerite crystal and grind it perpendicular to the fourfold symmetry axis, and we mounted it in the apparatus. We now had a goniometer as part of it, etc.; the instrument was now much more complicated and finished. Also, different sections of sphalerite, cut in different directions, were examined. We took another picture with a long exposure time. And behold, the beautiful fourfold symmetry was there.

The first published X-ray diffraction pattern along the fourfold axis of sphalerite (Friedrich et al. 1912).

Now you can imagine the great joy! But here was the situation: Max Laue had intuited the phenomenon but did not yet grasp the theory. That’s why we had no idea what it would look like! We expected it would be a blurry thing, and we had set up plates in all directions and were now surprised that suddenly there were very sharp interference spots. Now Laue sat down straightaway and tried to do the right thing as an optical physicist according to the classic theory of optics. That was the difference between him and Bragg, isn’t it true? He [Laue] developed the theory from the old theoretical formulas about interference, these empirical formulas, and in this way, he was now able to derive equations, which then contributed to the interpretation of this interference phenomenon... Later it was said that we planned it in this order, that his theory emerged, and then the experiments were performed. In reality, the experiments came first, and then the theory followed. That is a mistake, which may give rise to some misinterpretations of the entire history. That’s how it was. Editor’s note:

References:

|