- History Home

- People, Leadership & Service

- A Legacy of Excellence

- History & Impact

- Meetings Through the Years

- Resources

Obituary - Jerome Karle (1918-2013)Biography | Publications | Curriculum Vitae | Videos | Slides | Articles | Obituary

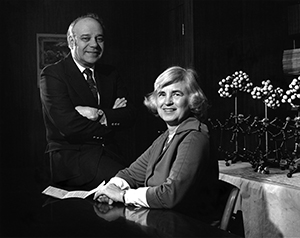

At Michigan, he met his future wife on the first day of a physical chemistry lab. Places in the lab were assigned alphabetically by last name, so Karle, Jerome was next to Lugoski, Isabella. They were married in 1942. At the U of M, Karle studied the diffraction patterns resulting from firing electrons at gases. After completing their dissertations in 1943, Jerome and Isabella moved to the University of Chicago to work on the Manhattan Project. Jerome returned to Michigan in 1944 to take on a research project for the US Navy, which involved studying the structure of hydrocarbon lubricants. In 1946, they moved to the US Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in Washington DC, where they remained until their retirement in 2009. Jerome was once asked why he had never joined the private sector, where his earning potential would have been much greater. "I'm not quite sure young people understand this," he said, "but it's quite possible to do good research for the Navy and the Department of Defense and at the same time do good science."

Initially, Jerome and Isabella continued to focus on electron-diffraction experiments. In parallel, Jerome made a theoretical analysis predicting what diffraction patterns to expect from oriented hydrocarbons, and this got him wondering about applying his theories to the analysis of crystal structures. It was around this point that the Karles were joined by Herbert Hauptman. The problem they faced was that although x-rays diffracted from crystals carry information that can produce a picture of the atomic structure, only part of that information is accessible experimentally. Only the amplitudes of the electromagnetic waves bouncing off the atoms can be observed by photon detectors; the phase offset of each periodic wave relative to the others cannot be measured. Fortunately, for typical crystals there are many more x-ray reflections than there are atoms, which implies that the reflections must be mathematically interrelated. Starting in 1950, Karle and Hauptman drew on fundamental knowledge about the nature of matter (specifically, that one cannot have negative electron density) to find mathematical relationships among the diffracted waves. Soon after, they established a probability theory, which they brashly announced in 1953 in an abstruse monograph entitled 'Solution of the Phase Problem'. Early reception of the Karle-Hauptman work was at best muted. Quoting Karle himself, "during the early 1950s ... a large number of fellow-scientists did not believe a word we said." The tide was turned by Isabella when she applied the work to challenging structures such as peptides. "I do the physical applications, he works with the theoretical," she told The Washington Post. "It makes a good team. Science requires both types." In 1966, Isabella and Jerome Karle published a landmark paper in Acta Crystallographica, which laid out step by step how to determine crystal structures. Others joined the venture with computer programs, and ever increasing numbers of ever more complex structures came to be determined through direct methods. By the time Karle and Hauptman received the Nobel prize, Karle had become prominent in crystallography circles; Jerome served as President of the International Union of Crystallography in the early 1980s, and was President of ACA in 1972. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1976; Isabella followed two years later.

As I discovered during my postdoctoral time with Karle in the early 1970s, the power of the statistical methods underlying his and Hauptman's approach is not unbounded (I tried with little success to apply his methods to protein crystals). Nevertheless, Karle's influence extends to macromolecules. He was fascinated by resonance in diffraction (whereby certain atoms behave anomalously when the energy of incident x-rays matches the energy of an electronic orbital), and he made seminal contributions to the theory underlying an approach now called multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD). MAD and SAD, MAD's single-wavelength counterpart, are now commonly used to determine macromolecular structures, such as membrane proteins. Both require that the resonant atoms be located as a first step, and the Karle-Hauptman direct methods are now the approach of choice for finding them. Karle's interests were broad, as suggested by the name he gave his unit at the NRL - the Laboratory for the Structure of Matter. The work there ranged from electron diffraction of gases to quantum chemistry of excited states, to the study of glasses and amorphous materials, and of course, crystals. Although these activities engaged several group members and were largely experimental, the Jerry I knew was a lone theoretician; he authored many papers alone and his main working interaction was with a computer programmer who tested his theories. Ultimately, Karle's major contribution was to allow researchers to shift their focus from the intricacies and challenges of crystallography to molecules and biochemical mechanisms. He turned chemical crystallographers into crystallographic chemists. The mathematical approaches that Karle and Hauptman established, known as direct methods, have helped researchers to elucidate the structure of key molecules such as vitamins and hormones, and to gain insight into biochemical mechanisms. Karle and Hauptman shared the 1985 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work. The awarding of the Nobel came as something of a surprise to Jerome. He was 39,000 feet over the ocean on a transatlantic flight when the pilot made an announcement over the loudspeaker. "We are honored to have flying with us today America's newest Nobel Prize winner, and he doesn't even know it. In fact, the award is so new that Dr. Jerome Karle, located in seat 29C, left Munich this morning before he could be notified that he was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry." In the cabin, he was feted with champagne. Survivors include his wife Isabella, of Lake Barcroft; three daughters, Louise Karle Hanson, a chemist, of Long Island, Jean Karle, also a chemist, of Vienna and Madeleine Karle Tawney, a geologist, of Lake Barcroft; and four grandchildren. Adapted from Nature, 499, p 410 (July 25, 2013) by Wayne Hendrickson with some additions from the June 14th Washington Post article by Emily Langer.

Remembrances of Jerome Karle From Greg Petsko: I always found Jerome helpful, friendly, and genuinely interested in every aspect of crystallography. He wore his considerable intellect well, like a comfortable suit of clothes, without ostentation or drama.

From Jane and Theo Hahn: We both were very sad learning of Jerry Karle's death. We knew the Karle family more than fifty years and were always very happy when we met "The Karles" at international crystallographic congresses. I will describe some of these meetings and, in particular, mention the long work for the International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) by Jerry. My first encounter with Jerry and Isabella Karle was in 1953 when I was a young post-doc at MIT with Martin Burger. There were many conferences in which Jerry and Isabella reported on the first steps of their work on "direct methods" of phase determination. It was particularly impressive to hear the theory from Jerry and the matching experimental structure determinations of complicated crystals from Isabella. Their marriage was grounded in love and crystals. This new theory impressed me greatly. One of the first books I bought in America - with my first dollars - was the monograph by Hauptman & Karle "The solutions of the Phase Problem I. The centrosymetric case". I remember vividly that this method was discussed very controversially in the crystallographic community at the time. What a wonderful beginning of their success story. The book still exists in the library of our lab in Aachen and is read by many students as a "classic" crystallographic text. In the subsequent years the general case - the extension of the phase problem from centrosymetric to non-centrosymentric crystals - was solved by Jerry Karle and Herbert Hauptman. We were very pleased that in July 1968 the entire Karle family of five visited us in Aachen and both, Jerry and Isabella, each gave a splendid lecture under the common title "Theory and practice of phase determination. Application to non-centrosymetric crystals" - that completed the story. The lecture was enthusiastically received and we all realized that the Karle-Hauptman method now has brought a breakthrough in the structure determination of crystals. One year later, in the summer of 1969, after the IUCr congress in Stony Brook, many "foreign" crystallographers (us included) were guests of the Karles in Washington, at a post-conference meeting with wonderful hospitality. We remember especially an excursion to the historic battleground of Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Jerry was president of the IUCr from 1981-84. I followed him 1984-87, with Jerry as past-president. The "turn over" took place at the congress in Hamburg. I consider these years as a high point in our cooperation. We regularly corresponded on matters of the Union per postal mail. Jerry was an excellent administrator and a far-sighted science-executive with a strong feeling for international problems and cooperation's and the needs of scientists in smaller, less privileged countries. He was highly regarded both for his science and his political expertise. It was during my presidency, in 1985, that Herbert Hauptmann and Jerome Karle received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. At the next IUCr executive meeting in Chester we had a big cocktail party for Jerry, but it was strictly called "Spring Party", everybody knew what spring meant. I last met the Karle family during the IUCr congress in Geneva. A special scientific event was the "trilogy" of the Karle family with lectures by J(erry), I(sabella) and J(Jean) Karle. What a magnificent good-bye to the scientific community with three lectures from one family. Jerry was a serious man, but with a dry sense of humor. I will close my contribution with a story: In the 19th century there was a German writer who wrote very popular books about the American west, well known by every boy between 8-80 years of age. Karl May. Curiously, he never spent any time in America, nor did he speak a word of English. Jerry had heard about him and asked me about his writings. As I knew Jerry was fluent in German, I sent him the famous volume "Der Schatz im Silbersee" (1890) in the original German. After a few weeks Jerry would write me back: I am absolutely flabbergasted that a man who was never in America can describe this country and its inhabitants so accurately. Well, Jerry now became an expert on American Indians. The two Hahn's will always remember our friend Jerry Karle. We send our very cordial greetings to Isabella and their three daughters. Jane and Theo Hahn, Aachen, Germany.

From Eaton Lattman: During the 1960s and 1970s there was a regularly scheduled Washington Crystallography colloquium, which met approximately once a month during the academic year. It was attended by crystallographers from all over the region, including a group of us from Baltimore who used to journey down whenever we could. Jerry and Isabella Karle were regular attendees at this meeting, and I got to know Jerry quite well through the conversations that took place over the dinners that usually followed the talks. I was a graduate student and then a young postdoc during many of the years that I went, and Jerry was always gracious, deeply interested in what I was doing, and a source of wisdom and friendly advice. It was always a pleasure to see him. I also remember that he was particularly fond of a French restaurant on Connecticut Avenue called Pouget's. He was particularly cheerful when the speaker chose that restaurant as our dinner destination.

From Jean Karle: My father enriched my life immeasurably. I have very many wonderful memories, of my father, but will limit this remembrance to crystallography related conferences and events. I was not at every ACA or IUCr meeting that my father attended, nor was he at all the ones I attended. I have counted 16 ACA meetings, 6 IUCr meetings, 1 ECM meeting, 2 crystallographic summer schools, and the 1962 Commemorative Meeting held in Munich, Germany, for Fifty Years of X-ray Diffraction that we both attended. I use the term 'attended' loosely. Before I became a practicing scientist, I attended meetings as an accompanying family member. In this capacity, the meetings were important to me as I visited many parts of the USA, Canada, and Europe, exposing me to new sights and cultures. I saw such a variety of sights from standing amid bubbling mud ponds in Yellowstone National Park after an ACA meeting in Bozeman, Montana, to touring Bavarian castles during the Munich meeting, to canoeing through the Rideau Canal during an ACA meeting in Ottawa, Canada. All meetings were memorable, but some meetings were firsts. My first meeting was the 1959 ACA meeting at Cornell University where I stayed for the first time in a university dormitory. To this day I remember an excursion to the Corning Museum of Glass seeing glass hand blown as well as the very swollen foot I had from stepping on a yellow jacket at a swimming outing. My first IUCr meeting was in 1960 in Cambridge, England. Most memorable was an excursion to a flint mine where one had to climb in and out of the mine via a very tall ladder. My last first occurred at the 1972 IUCr meeting in Kyoto, Japan, where I gave my first presentation at a scientific conference. My parents, sisters, and brother-in-law were all seated in the front row. (No pressure. . .) My father had this dream that I would give a presentation at a crystallography meeting, and since our first initials are the same, attendees would be expecting to hear a talk by my father, when instead it would be his daughter speaking. My parents almost spoiled the surprise by telling their friends, prior to my talk, that I would be speaking. However, one friend did not get the message and was surprised, thus fulfilling my father's dream. My father was always very supportive. When we sisters were young, he wanted us to spend summer vacations enjoying outdoor sports as well as the sights and cultures of the parts of the world we visited. When I became an active member of the scientific community, he was equally supportive of and proud of my work and presentations. I also proudly listened to my father's lectures. When he was describing the development of direct methods for crystal structure analysis, the method for which he was honored with the 1985 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, I realized it was evident that my father belongs to a select group of individuals who have a rare ability to understand non-apparent interrelationships of physical phenomena. This special gift includes the ability to recognize and use simple concepts to advance the interpretation of physical phenomena. His application of the principle of non-negativity, the concept that electron density at any point in space can be zero or positive, but never negative, provided a key element of direct methods. He first deduced the principle of non-negativity while performing electron diffraction analyses of molecules in the vapor state. My father's enrichment of my life was immeasurable. Being able to share Nobel week with him in Stockholm in 1985 is a memory I will never forget. Just after my family arrived, Stockholm was blanketed by a heavy snowfall covering the city with glistening crystalline snowflakes, appropriate for a Nobel Prize being awarded in crystallography. We had exquisite receptions, concerts, tours, dinners, and Nobel lectures capped off by the ultimate events of the Awards Ceremony and the Nobel Dinner. The King and Queen were most gracious hosts, not appearing bothered by my photography at the Nobel Dinner. When a daughter of another 1985 Nobel Prize recipient was asked what her Stockholm experience was like, she responded that it was like a fairy tale. I absolutely agree. The saying goes that we do not get to choose our parents. I will be forever grateful that my father chose to have me. |

Jerome Karle, who died on June 6, 2013 of liver cancer, was born Jerome Karfunkle on June 18, 1918 in Brooklyn, the son of immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father was a Coney Island businessman; his mother, a homemaker, was a pianist and organist. Jerome later changed his surname to Karle. A precocious product of New York public schools, he completed high school at just 15 years old and went on to the City College of New York. He graduated in 1937 along with Herbert Hauptman, (they did not know each other at the time), and Arthur Kornberg, another of City College's many Nobel laureates. He then went to Harvard where he gained a master's degree in biology. After spending about a year at the New York State Health Department in Albany, Karle pursued further graduate studies, this time in chemistry at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Jerome Karle, who died on June 6, 2013 of liver cancer, was born Jerome Karfunkle on June 18, 1918 in Brooklyn, the son of immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father was a Coney Island businessman; his mother, a homemaker, was a pianist and organist. Jerome later changed his surname to Karle. A precocious product of New York public schools, he completed high school at just 15 years old and went on to the City College of New York. He graduated in 1937 along with Herbert Hauptman, (they did not know each other at the time), and Arthur Kornberg, another of City College's many Nobel laureates. He then went to Harvard where he gained a master's degree in biology. After spending about a year at the New York State Health Department in Albany, Karle pursued further graduate studies, this time in chemistry at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.